Can Texas Gerrymander the Senate Too?

Are We Headed There? If So Precedent May Not Save You

How do you deal with the extraordinary when all you have is the old playbook? You start by imagining the unexpected. Each news cycle brings a new shock. At some point you try to get ahead of the curve.

In 2003 Texas Republicans took an almost unprecedented step of openly redrawing US House boundaries mid-decade, rather than waiting until 2011 after a new census, in order to gain more seats in the federal House of Representatives, which allowed them to take control of the delegation for the first time since Reconstruction. Now they are at it again in 2025. And they could go for broke. If they dare, they can further gerrymander Congress, drastically altering the balance in the US Senate by creating eight new GOP senators. How could they do it? Here is how the Texas GOP can rig the Senate in 2026, if they go all out.

The US Constitution allows Congress to admit new states into the Union; we all know that is how we grew from 13 states to 50 states in 1959 with the admission of Alaska and Hawai’i. However, not all of those states were from newly acquired or conquered land. The first new state was Vermont, which was disputed between the New Hampshire and New York colonies until the British Board of Trade, acting on behalf of King George III, set the boundary between the states at the Connecticut River. This made what we now call Vermont part of the colony of New York, and the folk of the Green Mountain State did not like it and did their best to ignore New York authorities. When independence was declared from King George III in 1776, the Vermonters wanted their own state and declared their independence from New York in 1777 claiming to be independent republic. This was neither legal nor recognized by the new United States; allowing locals to declare independence from states would have ruined the war effort against Britain. It may seem odd given what happened in 1776, but no one asserted the absolute unilateral right to declare independence or to join the USA without the consent of the state involved. When the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence, they did so knowing that their assertion would have to be backed up by force—that it was just beautiful writing and signatures on parchment—and that General George Washington had to make it real. He did. The Constitution was written, and the people of Vermont were technically included under the authority of the newly ratified US Constitution on July 26, 1788, as part of New York.

They were Americans, but they were not officially Vermonters, yet. Article Four, Section Three of the US Constitution reads:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

Let’s break this down: One, Congress can admit new states at will. Two, they can create new states out of a part of an old state. Three, you can actually combine any number of states into one unified state. And finally, Americans can split off parts of different states and combine them to make a new state. But no one can do this unilaterally; all the involved states’ legislatures, and Congress must agree but at its discretion.

Since Vermont was legally part of New York, the Vermonters had to get the government of the State of New York to agree. New York did not agree until 1790, and then Vermont was able to join the Union as a member state. After New York consented, the proud people of Vermont ratified the U.S. Constitution in January 1791 and were admitted as the 14th state on March 4, 1791.

Early in US history several states started as part of another state, such as Kentucky splitting from Virginia and Maine splitting from Massachusetts. There are other examples—mostly involving Virginia in the 1780s—but you get the picture: making new states out of existing ones is not a new thing. The dispute if one arose would not be over whether states could split but over how federal and state consent was obtained.

The one really controversial case was West Virginia’s creation. Only the areas represented in the loyal Union government of Virginia, aka the Restored Government of Virginia, meeting in Wheeling when it approved statehood for West Virginia in 1862; before it moved to Alexandria later in 1863, got a say in the matter. The rebels loyal to the so-called Confederacy occupied Richmond and most of the rest of the Commonwealth, as a result, the creation of West Virginia was done without all of Virginia having representatives who got to vote on the split and at the time was legally contentious. Even Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet split on West Virginia’s creation with half advising the president for and half against it, the president himself hesitated, but agreed to the admission of West Virginia as an expedient of war and concurred with Congress. But for some the move remains a matter of legitimate dispute.

But this history gives the GOP a weapon against the Democrats to maintain absolute control of the US Senate: split Texas into five states with automatic Congressional approval and have eight new GOP senators appointed or elected in 2026. How?

Back in 1836, the American settlers in Texas defeated the Mexican forces and won their independence. They sought to join the Union, but with Northern skepticism about a new, huge slave state and disapproval over the war itself, Congress refused. So, Texas had to wait until 1844, when James Knox Polk won the presidency on an expansionist platform that gave electoral approval to a plan of annexation. Texas was ready to end its status as an independent republic and join the Union. But now it was an independent country, so some thought it required a treaty, and the lame-duck president, John Tyler, did not want Polk to get credit, so he tried to push a treaty of annexation through before Polk took office. It failed in the Senate. So he fell back on Article Four, Section Three, and went for a Congressional resolution admitting Texas as a state. Contrary to widely held belief, Texas cannot unilaterally secede. But Texas might be able to act uniquely and (functionally) unilaterally on division—and it can checkmate the Democrats’ dreams of taking the US Senate: The GOP can argue that Texas does not need new Congressional approval to split and make new states. Congress already gave it.

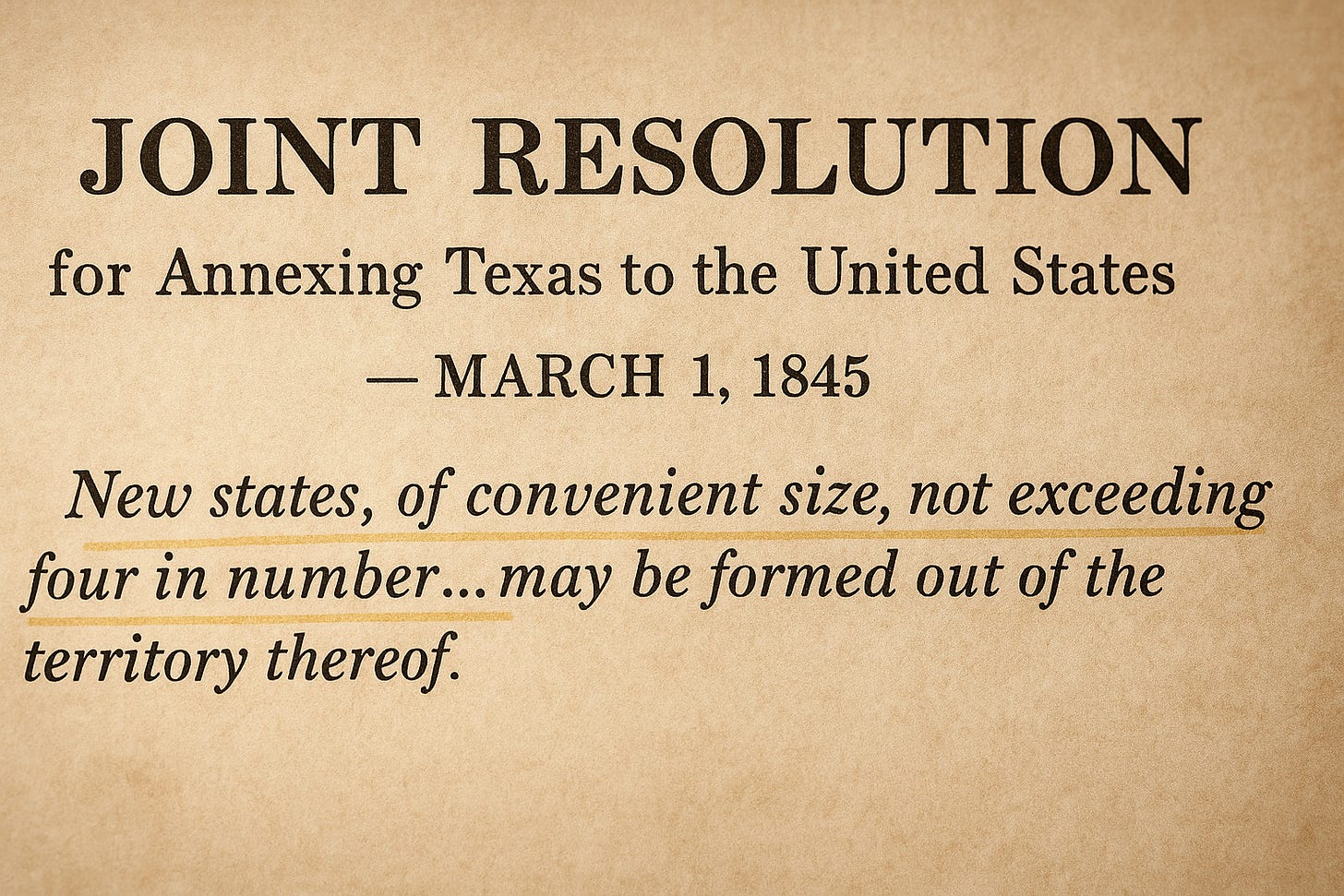

The resolution passed by House and Senate and signed by President Tyler on March 1, 1845, reads:

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Congress doth consent that the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to the Republic of Texas, may be erected into a new state, to be called the state of Texas, with a republican form of government, to be adopted by the people of said republic, by deputies in Convention assembled, with the consent of the existing government, in order that the same may be admitted as one of the states of this Union.1

2. And be it further resolved, That the foregoing consent of Congress is given upon the following conditions, and with the following guarantees, to wit...

That is the opening of the resolution which then goes on to list three conditions and guarantees, the third is critical as it reads:

Third- New states, of convenient size, not exceeding four in number, in addition to said state of Texas, and having sufficient population, may hereafter, by the consent of said state, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the federal constitution. And such states as may be formed out of that portion of said territory lying south of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude, commonly known as the Missouri compromise line, shall be admitted into the Union with or without slavery, as the people of each state asking admission may desire. And in such state or states as shall be formed out of said territory north of said Missouri compromise line, slavery, or involuntary servitude, (except for crime,) shall be prohibited.2

In June 1845 Texas accepted the terms:

Whereas the Government of the United States hath proposed the following terms, guarantees and conditions on which the people and Territory of the Republic of Texas may be erected into a new State to be called the State of Texas, and admitted as one of the States of the American Union, to wit:… Third, new States of convenient size, not exceeding four in number, in addition to said State of Texas, and having sufficient population, may hereafter, by the consent of said State, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provision of the Federal (constitution. And such States as may be formed out of that portion of said territory lying south of thirty-six degrees thirty minutes north latitude, commonly known as the Missouri compromise line, shall be admitted into the Union, with or without Slavery, as the people of each State asking admission may desire. And in such State or States as shall be formed out of said territory north of said Missouri compromise line, slavery or involuntary servitude (except for crime) shall be prohibited. And whereas, by said terms, the consent of the existing Government of Texas is required,-Therefore,

Be it resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Republic of Texas in Congress assembled, That the Government of Texas doth consent that the People and Territory of the Republic of Texas may be erected into a new State to be called the State of Texas, with a Republican form of Government to be adopted by the People of said Republic, by Deputies in Convention assembled, in order that the same may be admitted as one of the States of the American Union; and said consent is given on the terms, guarantees, and conditions set forth in the Preamble to this Joint Resolution…3

So, in 1845, Texas accepted both the legitimacy of the Missouri Compromise and that it could divide, at will without a new consent vote, so Republican the argument would go, into an additional four states. These were the terms, conditions, and guarantees that a then sovereign foreign state, the Republic of Texas, agreed to when it joined the American Union. The later December resolution of Congress under the new US President James Polk references and accepts the one from March which Texas consented to in June while clarifying that Texas would be on equal-footing to other states; meaning would Texas enjoy equal rights to the other states:

Whereas, the Congress of the United States, by a Joint Resolution approved March the first, eighteen hundred and forty-five, did consent that the territory properly included within, and rightfully belonging to the Republic of Texas, might be erected into a new state, to be called The State of Texas, with a republican form of government, to be adopted by the people of said republic, by deputies in Convention assembled, with the consent of the existing government, in order that the same might be admitted as one of the states of the Union; which consent of Congress was given upon certain conditions specified in the first and second sections of said Joint Resolution: And whereas, the people of the said Republic of Texas, by deputies in Convention assembled, with the consent of the existing government, did adopt a Constitution and erect a new state, with a republican form of government, and in the name of the people of Texas, and by their authority, did ordain and declare, that they assented to and accepted the proposals, conditions, and guarantees contained in said first and second sections of said resolution: And whereas the said Constitution, with the proper evidence of its adoption by the people of the republic of Texas, has been transmitted to the President of the United States, and laid before Congress, in conformity to the provisions of said Joint Resolution..4

Texas Argument: “Equal footing” set Texas’s sovereign status at admission; it did not repeal Congress’s earlier approval of division into four additional states.

“That would not fly” you might say, to which I would suggest that the year 2025 is not impressed by your denial. Furthermore, with the current Supreme Court’s oddly reasoned positions in critical disputes recently, and the Texas Republicans’ willingness to trade on their cowboy bravado to push POTUS’s agenda, it is a bad idea to rest your hopes on disputed precedent. Today, Republicans in Texas, led by Governor Gregory Wayne Abbott, have already reset their electoral maps to gerrymander more Republican US House seats to suit their party leader US President Donald John Trump. If they are willing to go for it, they can further shift Congress by drawing five maps to create eight new legitimate US Senators at will and make us a 54-state union. Four new states, eight senators, five lone stars, 108 senators. The Democrats will of course fight this in the courts, but those who dismiss the potential may be setting themselves up for shock and disappointment. In unprecedented times, history teaches us to be humble not overconfident. If it comes up it would be a legitimate dispute that cannot just be waved away.

This is not a novelty of internet lawyers, Texan leaders embraced the idea and debated it from the beginning. The “Divisionists” tried early and often: an 1847 East/West plan collapsed after the death of Isaac Van Zandt the republic’s envoy turned leading gubernatorial candidate who was running on dividing Texas into more manageable smaller states.5 Van Zandt had been a Texas diplomat in Washington during the annexation negotiations, and he had pushed for the four-state provision. He was the favorite to win the governorship and implement his plan when he died of yellow fever. Before and after the Civil War the plan was debated and rejected never coming as close as it did in 1847.

In the twentieth century the banner passed to John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner, the Uvalde congressman who argued Texas should become five “great States” and claim ten senators—insisting the 1845 clause pre-approved division.6 Garner thought it wrong that a big and growing state like Texas would become greatly underrepresented in the Senate compared to the small New England states. Garner was the Democratic Leader in the US House, then Speaker after Democrats took control in the 1930 Great Depression midterms, and after FDR’s landslide in 1932 he was vice president, FDR’s longest serving. Not a minor voice. This idea has fallen out of favor in the last century, but that does not mean it is too wild for 2025, it is the year of wild ideas.

The argument by opposed Constitutional scholars will be that the line “which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the federal constitution” will allow Congress to assert the right to approve or reject the plan under Article Four, and there are members of the GOP caucus who would balk at creating new states. One should not be too presumptive about partisan outcomes, and there is a plausible answer to this that the Texas GOP could argue: the US Constitution already explicitly allows the creation of new states in an unlimited number, so there was no reason for Congress to insert a number for Texas, which it did, and then to state that these hypothetical states could enter the Union under the provisions of the Constitution unless that is pre-consent for Texas to create not more than four additional states without additional approval. If it were merely a restatement of the Constitution, it would be odd, redundant, and would not have a numerical qualifier they could argue. Further, Texas accepted this as a unique but not exclusive guarantee, should it wish to exercise it. Likewise the Republicans would latch onto the words “entitled to admission” to argue that it helps their case not that of their opponents. Additionally there is the history of prominent men disagreeing over the whether this would lead to automatic recognition and admission of the new states, with many Texans holding the view that this is in fact what was intended when negotiated.

While the annexation of the Texas Republic by resolution and not treaty was unusual, the 19th century Supreme Court accepted that the resolution made Texas an irrevocable part of the Union. The resolution holds. The dispute is over whether Texas would have to seek additional approval for its new “little star” states to join the Union and there is a case that it does not. If the GOP thinks they will lose the Senate in 2026 this might stop being fantasy.

The Democrats cannot match this play because they do not have Congressional pre-consent to split say California or New York, are not likely to get it, nor do they have a Supreme Court that would accept Virginia’s potential challenge to the legality of West Virginia and take two Senators from the GOP, leaving Mark Warner and Tim Kaine to represent a Reunited Dominion. But if the Republicans in Texas take that route because Trump tells them they have to do so to preserve his revolution, then the Virginia play becomes the only one the Democrats could reasonably make, and it is a long shot to say the least. The other desperation move would be for more Californians and New Yorkers to move to Texas. But the fact is this is an asymmetrical move with the advantage to MAGA.

With aligned Congressional leaders, facts on the ground can precede—and shape—the litigation.

Nate Silver looked at this idea in the saner days of 2009 and concluded that a reasonably redrawn Texas of five-states would help the Democrats in the Electoral College but hurt them in the Senate and so concluded that Texas Republicans would never do it.7 Others argued that the division of Texas wealth would stop it. But these are not reasonable times. The blatant nature of the US House redistricting means that additional escalations have to be considered as real possibilities