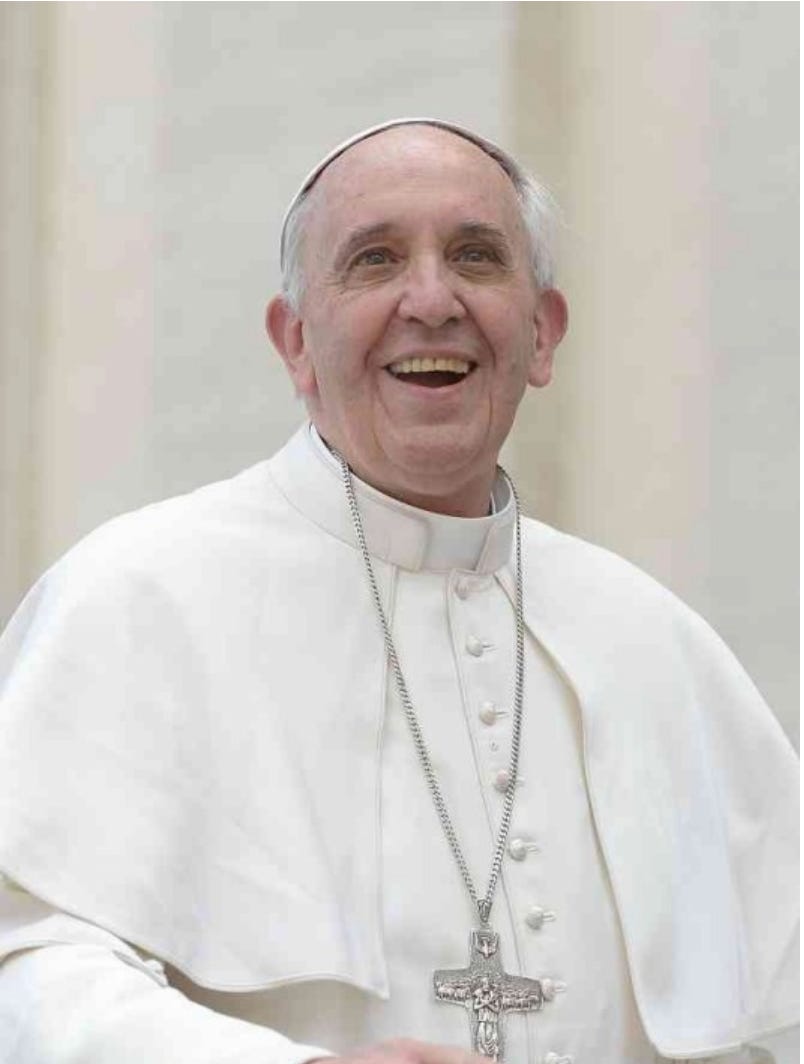

Requiescat in Pace: Jorge Mario Bergoglio | Pope Francis AD1936-2025

Dear Reader,

Sorry, for the late Message Mondays post, I changed my original posting plans due to the passing of the Roman Pontiff.

“VATICAN CITY—Pope Francis, who sought to refocus the Catholic Church on promoting social and economic justice rather than traditional moral teachings but presided over growing divisions in the church and struggled with the lingering scandal of clerical sex abuse, has died, the Vatican said. He was 88.”

It is rare that a single sentence so thoroughly captures a moment of confusion, amnesia, and moral disarray.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who later became Pope Francis, died on Easter Monday, April 21, 2025, at the age of 88. It is the irony of the Curia that after the Polish John Paul II and the German Benedict XVI that the first pope from the Americas was born to an Italian immigrant father, and a mother who was Italian-Argentine. He is known for the belief that if one truly follows Christ, then their conscience knows that “trampling upon a person’s dignity is a serious sin.”

He was born in Buenos Aires on December 17, 1936. Before becoming a priest, Pope Francis graduated as a chemical technician and then entered the Diocesan Seminary of Villa Devoto. He was inducted as a novice of the order of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, on March 11, 1958. His interests were varied; he taught literature and psychology from 1964-66. He was finally ordained a priest in December 1969. His formation included philosophical and theological studies in Argentina, Chile, and Spain, followed by decades of service as a teacher, rector, spiritual director, and eventually provincial superior of the Jesuits in Argentina on a steady rise through the ranks. Eventually, he became the protégé of Cardinal Antonio Quarracino, Archbishop of Buenos Aires during the pontificate of John Paul II.

He became Auxiliary Bishop of Buenos Aires in 1992, Coadjutor Archbishop in 1997, and Archbishop and Primate of Argentina in 1998. Pope John Paul II created him a cardinal in 2001, making him a Prince of the Church. Yet, Bergoglio as Pope Francis in 2017 reminded newly elevated cardinals of the meaning of duty to Christ, declaring that:

“He does not call you to become 'princes' of the Church, to 'sit on his right or on his left.' He calls you to serve like Him and with Him.”

Upon becoming a bishop, his motto was miserando atque eligendo, meaning “By having mercy and by choosing him,” referring to Jesus having mercy and calling the tax collector to follow Him. The story is from the Gospel of Matthew, important to Francis because his conversion experience and full confession of faith came on the Feast of St. Matthew when he was 17 years old.

Known for commuting by bus, living in a modest apartment, and cooking his own meals, Cardinal Bergoglio embodied the Jesuit ideal of simplicity and service. His theological outlook was marked by a distrust of clericalism, a call for mercy, and a vision of justice grounded in the Catechism, the Ten Commandments, and the Beatitudes. He emphasized evangelization, enhanced lay education and leadership, and solidarity with the marginalized, initiating city-wide missionary programs in Buenos Aires. During the 2001 Argentine financial crisis, he was a voice of conscience during the turbulence.

On March 13, 2013, he was elected Supreme Pontiff and Bishop of Rome, taking the name Francis, in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi. It was a clear signal that his papacy would be a commitment to humility, peace, and care for the poor. He was also the first Jesuit to preside over the See of Peter. Some have alleged that his pontificate will be remembered for its striking contradictions: a humble pastor with global stature, a reformer who stirred resistance within the Curia, a pope beloved by progressives yet rooted in distinctly Catholic idioms. He called the Roman Church to the margins while presiding over mounting tensions within its center. In the words of both admirer and critic, he was a pope who unsettled, challenged, and provoked, but I argue that if that description is accurate, then he did so not by abandoning tradition, but by pressing the faithful to remember parts of it the modern world prefers to forget.

Francis leaves behind a legacy of exposing confusion: praised by many for his compassion and global moral witness, questioned by others for seeming ambiguity and perceived shortcomings in confronting abuse and doctrinal drift. Yet to reduce his papacy to progressivism or politics, as so many headlines do, is to misunderstand both the man and the Chair he occupied.

So what’s wrong with the WSJ obituary?

What is troubling about the obituary’s framing is that it reflects the way modern political categories have colonized even our religious understanding. “Social justice” is read through the lens of progressive politics, while “traditional moral teachings” are reduced to the newest versions of the old Moral Majority’s culture war fights. But the Church’s moral galaxy is not a quadrant on the Venn diagram. Moral reality is too complicated for Right versus Left, the beauty of justice is too vibrant to be shaded by our partisanship.

The "social" in social justice refers to the structures, systems, and relationships within society that shape how goods, rights, and responsibilities are distributed. Unlike what could be called “simple" or commutative justice, governing concepts of individual transactions like in commerce, social justice deals with the common good, ensuring that every person has access to what they need to live with dignity as part of a community. But to the Christian tradition, social justice is simply justice, and the “social” is merely a modifier to clarify the scope of what one is discussing at a particular time. For some, social justice is a virtue, for others it is a slur, but for Francis, it was part of his ministry to reform the individual and therefore society, which is a collection of individuals. We can drop the modifier and ask how Francis related justice to the traditions of the Church.

Pope Francis did not trade traditional moral teaching for justice activism. He insisted that justice is a moral teaching. And in that insistence, he stood not outside tradition, but squarely within it. For Christians, and especially for those of us grounded in the classical and biblical traditions, justice has never been separate from moral teaching. It is moral teaching. Justice is not a boutique concern for the social scientist or the activist—it is a central virtue, a defining feature of the rightly ordered soul and the rightly ordered society. Consider John the Baptist’s message in the third chapter of Luke:

And the crowds asked him, “What then shall we do?” And he answered them, “Whoever has two tunics is to share with him who has none, and whoever has food is to do likewise.” Tax collectors also came to be baptized and said to him, “Teacher, what shall we do?” And he said to them, “Collect no more than you are authorized to do.” Soldiers also asked him, “And we, what shall we do?” And he said to them, “Do not extort money from anyone by threats or by false accusation, and be content with your wages.”

As the people were in expectation, and all were questioning in their hearts concerning John, whether he might be the Christ, John answered them all, saying, “I baptize you with water, but he who is mightier than I is coming, the strap of whose sandals I am not worthy to untie. He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.

In preparing them for the coming of the Christ, John told his questioners to stop participating in systemic corruption. He did not give the soldiers a pacifist message, no, he told them to keep doing their jobs but to be content with their wages, not to use their power to victimize and extort. Likewise, if Christendom was/is the international Christian community, then it necessarily has a moral order, a shared vision of the good, a common end, and thus a sense of justice. Not just justice between individuals, but a public, communal commitment to ordering society toward virtue and truth. It is a core assumption of Thomas Aquinas. If humans are made in the image of God, then they are created for good, not just utility. So society should seek the common uplift and betterment of all, not an unsophisticated push for the most efficient form of economic extraction.

The Beatitudes are a social vision. But more directly, Jesus Christ explained in the 25th chapter of Matthew how not only individuals but nations would be judged by God:

“When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne. Before him will be gathered all the nations, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. And he will place the sheep on his right, but the goats on the left. Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.’ “Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me no drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not clothe me, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’ Then they also will answer, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not minister to you?’ Then he will answer them, saying, ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

The ministry of Christ was full of repeated warnings against the rich and their self-indulgent and spiritually self-destructive behavior. So, for Pope Francis, the work of Christ was beyond “social justice” and much bigger because the traditions of the Church have always emphasized the rule of God over all creation: the personal, the social, the economic, the political, all things are under God. That’s what Saint Paul meant in the 13th chapter of Romans:

Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, for he is God's servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God's wrath on the wrongdoer. Therefore one must be in subjection, not only to avoid God's wrath but also for the sake of conscience. For because of this you also pay taxes, for the authorities are ministers of God, attending to this very thing. Pay to all what is owed to them: taxes to whom taxes are owed, revenue to whom revenue is owed, respect to whom respect is owed, honor to whom honor is owed.

The proper social order is a two-way street. A government to be legitimate must be just, and the people must obey that government. If the people disobey, they are criminals, but if the government does not pursue justice, ignores public order, and it is not honorable, then it is no longer a government acting as the servant of God; it has become a disorder thing. In which case is it not right for a Pope, or any Christian, to call it to correction?

What we call modernity has untethered justice from its moral roots. What remains is a hollowed-out version of the term, a system of rules with outcomes, statistics, and conveniences, not a grounded justice. Once, justice was defined by the common good; now, it is individual grievance and self-serving retribution. This is not justice. It is sentiment dressed up as ethics. The challenge has always been that the Church’s traditional moral teaching says that power is never enough, that might does not make right, and wealth does not make you a more valuable human being. Those with power and wealth have always been troubled by this message. Yet, because Christian thought conquered antiquity and dominates the Western world, the potent and connected, especially in the USA, devote significant time, resources, and energy to labeling economic and social justice as things that are un-Christian, Marxist, or anti-Christian. These are the occluding arts of godless technocratic capitalism.

To see this mistake applied to Pope Francis is especially telling, because while his critics and defenders alike caricatured him as a radical break from tradition, his deepest instincts were traditional in the truest meaning of the word: the received teachings of the Church. His emphasis on the poor, on the marginalized, and the dignity of labor was not a Marxist appropriation of the Church—it was a return to its roots. It called back to Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, which dealt with troubling developments in both industrial capitalism and socialism. It fit with Pope John Paul II’s Laborem Exercens, which warned of the need to maintain the dignity of work in a world transformed by machines and computers, which was itself inspired by Rerum Novarum.

Americans broadly once understood this synthesis, at least in its better moments. Our civil tradition—rooted in Protestant moralism and classical republicanism—once spoke fluently the language of virtue and justice together. Abraham Lincoln did not separate moral order from political action. The African American Protestants’ push for abolition and civil rights appealed to explicitly Christian assumptions about human dignity; it was a demand that the nation live up to the moral law it professed to believe. So when a major media outlet reduces the late pontiff’s public ministry to a supposed shift from moral theology to economic justice, it tells us more about the impoverished vocabulary of the age than about the man himself. The constant social media parsing of Pope Francis’s twelve years as head of the Roman Catholic Church exposed that much of the Western Christian world, including confirmed Catholics, had forgotten their moral history, or perhaps more to the point, they had never learned it.

Despite recent health challenges, including a hospitalization for double pneumonia earlier in the year, Pope Francis appeared in public on Easter Sunday, greeting crowds from the popemobile in St. Peter's Square. Perhaps his passing the day after Easter is fitting and a sign of the new times in the West. His native Argentina has declared a week of mourning.

Pope Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires in 1936, passed away in his residence in the Domus Sanctae Marthae, the modest Vatican residence he chose over the Apostolic Palace, today on Easter Monday, April 21, 2025, 7:35 a.m., at the age of 88 after suffering a cerebral stroke. He lived for the simplicity of the Gospel at a time of moral confoundment.

Requiescat in Pace

Hi Albert, a small point of disagreement. You argue that the Sermon on the Mount is a social (meaning here a group whether as small as perhaps even a family or as large as the "global village.") instruction. It may have that effect, especially in our age of totalitarian impulse, whether on the left in the form of wokeism or on the right and it's rejection of all thing even faintly colored in woke. This is not the totalitarianism of the Bolsheviks with their gulags and bullets to the head in the basement of Lubyanka nor is it the totalitarianism of the Nazis with their concentration camps and gas chambers. Rather it is totalitarianism in a velvet glove and an I-phone. But it is totalitarianism none the less. Neither side will brook dissent or difference, even the modern trend toward expressive individualism is totalitarian, you can only express the "acceptable" range of individualism, acceptable to the woke or anti-woke.

But I would argue that the Sermon on the Mount, like the Christian faith in broader terms is primarily an individual call to action, granted individuals united, by the shared faith, in human institutions, but none-the-less an individual call to action. Modern Christianity in its many forms is however not really Christianity, it is for the most part Moral Therapeutic Deism, for that the Sermon on the Mount is most assuredly appropriate as a social injunction. But God did not create "society" nor did Christ come to save "society" -- we are created as individuals and saved as individuals, I would argue that our salvation is based firmly and solely in Christ, but that our salvation is worked out as individuals through the gift of the Church and the Mysteries (Sacraments). The MTD error is the error of Jewish theology and culture, under MTD we are to make the world a better place first and foremost. But Christianity is about Albert and Doc, your wife and mine as individuals. This is why the Church in its infinite wisdom has determined that even a sinful priest can deliver the Mysteries with their full beneficial effect on behalf of Christ to us, if we are faithful in our bearing of our individual crosses, the state of the clergy while important is not critical. Christianity is not about saving the world it is about, first fixing ourselves, then our families and so on up the ladder. The Sermon on the Mount is useful for those steps up the ladder, but it is a personal injunction to fix ourselves, without that the Sermon on the Mount becomes nothing more than fuel for political action, twisting the meaning to suit the emotions and politics of the day.

We need to focus in this time of tumult and chaos, of liquid modernity, on fixing ourselves, of living out the Sermon on the Mount in our daily personal lives. The world like the poor will always, at least until the Day of the Lord, be with us. And even John the Forerunner's admonitions speak to that. If you have two (count 'em two) cloaks give one to your neighbor if he needs it, he doesn't tell us to strip ourselves naked to clothe our neighbor. He doesn't tell the soldiers to beat their swords into plowshares and to stop fighting and by implication killing our neighbor, no John the Forerunner was if nothing else a realist --he knew "fixing the world" was above his and our paygrade -- he instructed those who came to him, just as Christ did in the Sermon on the Mount, to fix themselves with God's grace.

If enough of us quit worrying about fixing the world and focus instead on fixing ourselves and in doing so draw more people to Christ, we working with God in syngery can begin to restore the world. For once I agree with the social historians in our field -- bottom up. But then as someone who was raised Irish Catholic, I struggled with my Irishness and Francis. I was always taught to love the Pope, but then never to listen to a word he said. It's easier to do both when what the Pope says at least makes sense. I think the folk over at Lutheran Satire got it right with their satirical take on a radio call in show with Hippy Pope Frank -- "what his holiness meant to say is...."