Origins of Black History Month

A Story of American Resilience

Virginia has produced some of the most important African Americans in history. From Douglas Wilder, the first elected Black governor of a U.S. State, and the famed Booker T. Washington. But to me, one who needs more attention is the great Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson, born exactly one decade plus a day after the proclamation of the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery in America forever. He was perhaps the first great black historian to look in-depth at European war and strategy. He wrote his master’s thesis at the University of Chicago on “The German Policy of France in the War of Austrian Succession.” Brilliant topic! For his dissertation at Harvard, he wrote about our home state in The Disruption of Virginia. Working his way through his doctoral program, Woodson taught high school history, English, French, and Spanish in Washington, DC. He became only the second Negro, after W. E. B. Du Bois, to receive a history Ph.D from Harvard. Two, only two! Even after completing his dissertation he continued to teach high school as no university would hire him. You see, Woodson was too hot to handle because he believed that Black history, then known as Negro history, should be professionally studied as a full discipline.

In the 1910s, it was the high point of segregation and the low point of national solidarity; scholars call this period the nadir of race relations. Dr. Woodson was a dues-paying member of the American Historical Association, the premier professional organization for the craft in the United States. Yet, because he was Negro he could not attend conferences nor present papers. Why be a member, then? Why send them your money? Who pays money to be disrespected? Woodson had a solution; he would create his own organization, not to complain to the Whites but to do the work of studying African American history: he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in September 1915, the year African Americans nationally and especially in Chicago celebrated the 50th anniversary of Emancipation. Now named the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), it has survived for 109 years and just had a fantastic conference in Pittsburgh last year.

Today, white American thinkers talk of life in the Negative World or of a Benedict Option, but I have long held that by not looking at Black history, they are missing key components of the history of their own country. Lessons of survival, ingenuity, and resilience. Black Americans had to create alternative modes of being because they were oppressed in a country that claimed to be home to liberty and freedom and was often impervious to legitimate criticism. Woodson determined that Black history was not about recognition from the rest of American society. Rather, it was far more important. It was about Black Americans learning their history for themselves and from themselves. It was independence and good old American self-reliance. The Association exists to educate our community, but all are welcome. Woodson hated propaganda, and much of American history at the time was white American hagiography. Woodson likely would have despised the 1619 Project because it contributed to propaganda more than history, as noted by the brilliant Dr. Daryl Michael Scott, Woodson scholar and former president of ASALH.

Woodson believed that the antidote to white propaganda was not Negro propaganda but good scholarly history. Basically Black historians needed to be focused on truth and strive for objectivity. So, he built an institution where they could support one another. But it was and remains a unique academic organization because many of the members are lay members of the community, not professional historians at all. What good would an elitist or strictly academic organization be at a time when government-mandated segregation was the norm, most Black Americans lived in the South and did not finish high school, and few contemplated college even in the more tolerant North? So, it became an organization of the people, where the scholars were held to account by the people they intended to serve. The Association was a level playing field, and ASALH has striven to maintain that in recent years. Some of the best academic panels I have ever attended have been full of the community member standing up and asking tough questions of the eggheads. I hope Woodson would be proud of the job I have done on two panels and chairing a third. But he also knew that the institution and its academic journal, the now called the Journal of African American History, could only do so much. The Association and the Journal could promote and publish original research, but more was required.

Respect for Black history would come from producing good history and reading ourselves, not pleading or begging for acceptance. Strength of scholarship and a will to honor our past would win the day, not appeals to pity. The Great War broke out, America joined, Woodson kept working, and the Journal got going. The Depression hit, and institutional support went down, and the Journal kept going. The Second World War and again, Carter G. Woodson remained undaunted. No Journal issues were missed. But he learned that fear of riling of Southerners made publishers reluctant to put out books that made Black folks look good or equal to whites. So Woodson founded the Associated Publishers and published books himself.

Still, not enough, the Welsh-born immigrant and sociologist Thomas J. Jones went out of his way in the early 20th century to infiltrate American organizations that served or engaged the Negro community where possible to remove Blacks from positions of authority. His attacks and whisper campaigns against Woodson caused the Association and Journal to lose support and donations from white American philanthropists who, at the time, were the traditional financial supporters of African civic and civil rights organizations. Gladly and ironically, Woodson already had a way to make the movement to support Black history scholarships self-funded: in 1926, he inaugurated Negro History Week in the second week of February.

It was about Black Americans learning their history for themselves and from themselves. It was independence and good old American self-reliance.

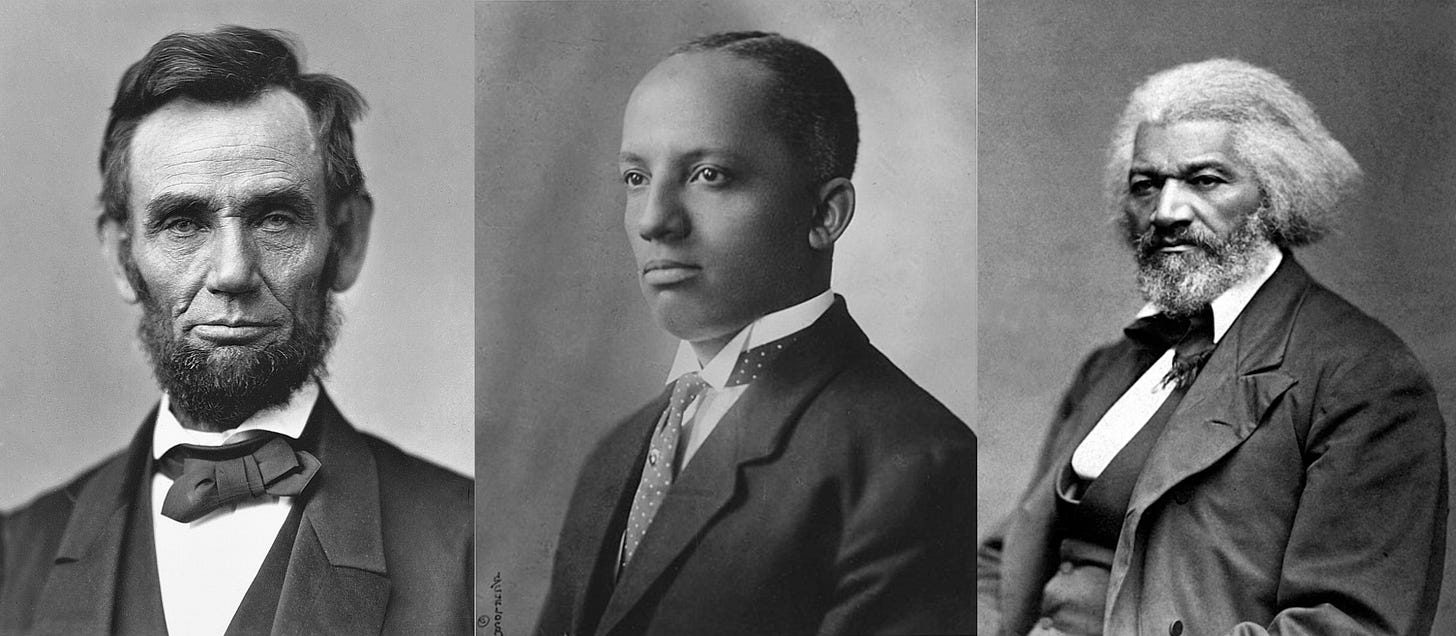

Every so often, you hear that “they made Black History Month the shortest month.” Complete nonsense. “They,” whoever that is supposed to be, did nothing of the sort whatsoever. Woodson chose a week in February because he wanted to honor the President who won the Civil War and freed our ancestors by joining the great cause of freedom and Frederick Douglass, the great freedom fighter; Lincoln’s birthday is February 12, and Douglass is two days later on Valentine’s Day. Black Americans had celebrated both days for decades, so it was the perfect time to celebrate Black history nationally. It would not become a government-sanctioned heritage month for fifty years when President Gerald R. Ford designated it as such as part of the 1976 Bicentennial celebrations for American Independence. It took off, and the attention from the community brought in small donors, individuals, and families who wanted to support the study of their history. It was organic, it was real, it did not need the government. By the time Woodson died in Washington, D.C., on April 3, 1950, Dr. Woodson had built a lasting tradition that in postwar America was even attracting white celebrants outside the South and was sweeping Negro schools.

A decade after founding Negro History Week, Carter G. Woodson set up the Negro Bulletin to publish the achievements of Black high school students and other members of the community. Back against the wall, discounted by his profession, Dr. Carter G. Woodson did not need to tear something down; he stood tall and created something new. It is still here. The Association and the Journal? They are still here. Happy African American History Month.

Thanks for this great article. It's nice to now the basis of the name of DC's Woodson High School

I have always respected Dr. Woodson yet it wasn't told in the South about why February was chosen as Black History Month .Thank you Albert for renewing my confidence in speaking more about Black History Month!